PAGE 9

The Japanese kept about 100 ducks in pens near their guard house and each day they would be let out and tended by three or four prisoners. Occasionally, some ducks would wander into the camp confines. The ducks usually were kept to the grass in the Japanese area between the guard house and our huts where they would pick up grubs etc to augment their daily diet of scraps from the Japanese kitchen. At the end of each day, they would be marched back into their pens for the night. The Koreans would try to count them in each evening but gave up eventually as the ducks would be running everywhere as they were shunted into their pens.

We all had visions of cooked duck and tried to think up ways of getting our hands on to one. A plan was eventually thought out by myself and came to me when I was squatting in the toilet block one day and heard the quacking of the ducks nearby. The toilet blocks were built in various parts of the camp in rows of six cubicles, in two rows with about a six foot "breeze-way" (or passageway) between. The cubicles had no doors and consisted of a plank of wood with a 12inch hole over the pit. As the ducks liked the white worms that infiltrated from these pits in their hundreds each day, it was not uncommon to see ten or twenty ducks around the toilet block. They should not have been in the camp but their keepers had a hard job of controlling them at times. Even though the ducks were in the camp off and on, it was difficult to catch one in the open as they would create such a racket with their honking it would soon arose the Jap guards either wandering through the camp or on the walls.

So one day I saw some ducks near the toilet block, I told Ken and Hughie Cory of my plan. I took up position inside one of the cubicles and Ken and Hughie quietly urged the ducks through the passageway between the blocks. As one passed my position, I leant out and grabbed it around the neck. So intent was I on making sure it would not make too much noise, I immediately screwed its neck. My actions were so severe the poor duck was dead in seconds. The other ducks took off with a flurry of wings outstretched and a certain amount of honking but it was all over so quickly that even Ken and Hughie did not realise the maneuver was completed and a dead duck lay at my feet in the cubicle. The keeper of those particular ducks did not see anything either - fortunately for me!

Both Ken and Hughie crowded around me as I carried the duck to our hut and cold-feathered it there, before taking it to a mate called Jimmy Bourne, who was one of the cooks in the kitchen. Quite a few of us had duck with our rice that night and all who participated in the so-called sumptuous meal spent half the night on the toilet, as our stomachs rebelled against the rich change in our diet. We will never know just what caused the upset tummies, for it could have been that our system was not able to handle such rich food after years of poor diet or perhaps those worm-diets the ducks so enjoyed gave them a strange quality. Whatever it was, we lost all interest in the ducks for the remainder of our stay in this camp.

We had the occasional concert here, put on by various prisoners and it was here that I met Les Graham who was an orderly with the 2/4 A.C.C.S. and was captured in the fall of Singapore and had been shipped to Burma and worked on the railway from that end. Les was quite an actor and both he and one or two others put on quite a few comical skits at these concerts. Even the Koreans and Japanese officers attended and they appeared to enjoy the entertainment as much as us. The Japs had allowed us to build quite a large stage and supplied material to allow the actors to have a small compartment for changing. The ingenuity of some of the prisoners was evident as eventually the stage and surrounds had quite a professional touch.

Malaria was still taking its toll on us all. I had so many relapses I lost count over the years. Although each one weakened me, I was fortunate not to suffer permanent damage. In many cases the type M.T. and S.T. affected the heart and brain and usually proved fatal. There was also an outbreak of Blackwater Fever in the latter days of our incarceration and it was this disease that took the life of one of our unit, Bill Blackwell of Victoria and incidentally the last of our unit to die. Poor Bill passed away only days before the surrender and had survived years of hardship to finally leave us so close to the end.

Our dislike for the Dutch was made even more evident in this camp by the devious ways they instigated in dodging the work-parties sent back to maintaining the railway. They invented all kinds of ailments that prevented the Japanese from putting them in the line-up. Some even grew beards that made them look older than their years while others put on a stooped attitude as though they were absolutely worn out and useless for further work. All sorts of ailments that were difficult for the Japs to prove were false. We knew of course, as they again appeared perfectly normal once a party had been assembled and despatched. Their answer to our bitterness over this was that they were rightly refusing to maintain an enemy supply route. However we all knew, including these Dutchmen, the Japanese would find men for these parties even if it meant taking sick men away and it was this attitude held by the Dutch, that caused a lot of our men being sent to make up the party even though they were in no fit state to go. Imagine our annoyance when, once the party was despatched, we would see these fitter Dutchmen openly bragging about how they fooled the Japs and got off the work-force party.

This was the first and only camp we were in, since leaving Java, that included nationalities other than Australian. I think we were most fortunate that during the tough days of the past years, we Aussies were on our own.. Very seldom did a man not pull his weight and I never saw one incident where a mate deserted another, or failed to help when needed. A type of special courage and mateship persevered throughout those days when men, even when reduced to the most dejected and utterly worn-out stage, still helped a mate survive to see another day.

Even the Koreans and Japanese I feel, secretly admired our loyalty to each other in such devastating circumstances and our ability to work in all conditions until the body gave out and was beyond our control. We saw other nationalities in camps we passed through, who had given up all hope and were left to die as they were of no longer any use to the Japanese as a work-force. British, Dutch, Indians. Javanese, Tamils etc in so many cases just could not handle the conditions. I feel that if we had been subjected to sharing a camp with these other nationalities in those days of hard labour and sickness, then perhaps it may have had its effect or some of us. As it was, I do not know of any man among us who did not think the Allies would eventually win the war and that if we tried hard enough, we would survive to return home. If any men did entertain other thoughts, for at the worst times one could not have blamed them, then they kept them to themselves.

It was one day, only a month or so before the end of hostilities, when Ken and I were loading up our litter of wood for the kitchen, that suddenly out. of the blue came a roar that almost deafened us! We cowered down as about a dozen Allied fighter-bombers roared over the camp and dropped bombs nearby. We heard machine-gun fire and saw clouds of smoke rise skyward about a mile or so from the camp. As suddenly as they appeared, they just as quickly disappeared, no doubt flying low in their departure.

The Koreans and Japs were racing around yelling all kinds of orders and everyone was made to stay in their huts. Ken and I made good time to our hut and there we were kept for the next few hours. We never did find out what was bombed or if the raid was successful or not. All kinds of rumours persisted of course, from supporting a parachute and sea-borne landing to the dropping of spies etc! All proved to be false of course. Over the previous year, we had seen high-flying Allied Liberator bombers pass over and in some cases pamphlets were dropped, mainly for the local population. I saw only one of these pamphlets in the latter part of 1944 and on it was a map of the Far East on one side and a map of Europe on the other. How disappointed we all were to see the areas in red still held by the enemy. Still a lot of Europe to be conquered and still fighting in New Guinea. This pamphlet did little for our morale.

It was in this camp that we were able to purchase a little tobacco. We, who had a job to do inside the camp, were paid a small sum of money for our efforts. Ken and I both pooled our money and sometimes the Thais were allowed to sell goods inside the camp and this was controlled by an officer appointed to a type of canteen duty. An unprocessed sugar was available, plus a native tobacco. I tried to smoke the tobacco as a cigarette, having used split paper as a covering. However the tobacco was too strong for me, so I followed the example of others and fashioned a pipe out of mango-tree root. These trees were growing in various parts of the camp and the root was found to be particularly good for the bowl of a pipe. The mouthpiece was fashioned from buffalo-horn, or toothbrush handles and the hole was inserted by heating a piece of wire. I quite enjoyed smoking the tobacco in the pipe and did so until our release. Incidentally I still have this pipe to this day.

Eventually the great day arrived!! We would hear the odd rumour that the war was over in Europe and that it was only a matter of time that all Allied armour would be focused on the Far Eastern conflict. These rumours were never confirmed and all we could do was live in hope that they had some foundation. However, the end came with a great deal of surprise as there was no cause for us to imagine it was close until, as it turned out, the 15th August 1945, the day hostilities ceased.

We noticed that day, that all Korean guards were wearing black shirts with their khaki shorts and had been issued with a pith helmet to replace the peaked cloth cap. Also we noticed that Japanese soldiers were replacing them as guards. This was unusual, but still no reason to believe it was over. However, that evening some meat and bread were delivered to our kitchen. Word soon spread that something was in the wind. That night we enjoyed fresh meat and bread for the first time in three and a half years! The whole camp was seething with rumours and hope! Questions were asked of our doctors and combatant officers, but nothing was confirmed. Although we were still made to keep inside our huts at night, I doubt if many slept for more than a few hours. I kept waking and men were talking for most of the night.

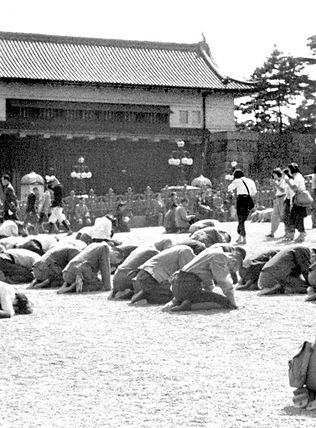

Next morning, 16th August, our breakfast was still pap, but this time supplemented with a slice of bread. Nobody could sit still long, only the very ill stayed in their huts - still rumours were rife, but still nothing substantiated. Then during the morning we noticed the absence of the Koreans. The guards were all Japanese! Also they began to talk to us and when we bowed, they said, "NO, no need - no need!" Now we were beginning to get excited! Around mid-morning some Japanese officers were driven into the camp and disappeared into the hut which was designated as Headquarters Hut for our senior officers.

All eyes were on this hut from then on, as men converged towards this area. Ken and I had just delivered our first load of wood for the morning. We were just leaving the kitchen on our way for the second load when a huge roar went up from the vicinity of Headquarters!! Then we saw a sight that will live in our memories forever! The Union Jack fluttered from a makeshift mast above Headquarters! Just then we also saw the Japanese Officers come out and were driven away. Now the whole camp was in an uproar!! Men were singing, shouting, and crying at the same time! Then Col. Dunlop and Col. Coates called to all to follow them to the concert area where they mounted the stage and told us to be quiet. They then informed us that the Jap. Officers had told them the war was over! It appears the Americans had dropped some devastating bombs on Japan and threatened to wipe out the nation if they, the Japanese, refused to surrender. So the day before had really been the day hostilities ceased.

However, we were told that, for our own safety, we should not leave the camp as there were probably pockets of Japanese soldiers around who would still be unaware of the surrender orders. Also we were told that certain officers would be allowed into the nearby village of Nakom Patom to purchase food for the camp and promissory notes would be accepted by the native population. For the first time in three and a half years we had no guards on the gates and no Korean or Japanese were in the guard-house or manning the walls. They had faded away and disappeared silently and unnoticed. Food began coming into the camp that afternoon, mostly white long-grained rice, (we had been living on poor quality unpolished rice) bread, pork, buffalo meat and fruit. That evening we had the most enjoyable meal of our lives! There was plenty of it and the cooks did an excellent job. Ken and I were only too pleased to keep up a good supply of wood to the kitchen.

Skeletal P.O.Ws

Messages:

Trying to contact an ex POW? Send me an email and I'll post them on here for you. Click here for some messages & info.

Any comments:

Email: G. Crew

glen@powerup.com.au

Jap Surrender